Even though I’ve been diagnosed with lupus for six years now, I recently came across this article from 2003 entitled The Spoon Theory by Christine Miserandino for the first time. I cried when I read it. Cried because there has never been a clearer explanation of what living with an invisible, chronic illness is like. Cried because seeing it dictated so bluntly made my reality…well, real. Cried because I realized I had been living like I had unlimited spoons for a while. Cried because I wanted more of them. I still cry every time I read it because it took me six years of living it, and someone else writing it, for me to finally understand what it means to be invisibly and chronically ill. I had to read it to be able to step back and see the difference between my former, healthy self, and my present self.

And, I want everyone else to read it. In fact, I think this article is so important, that I want it printed on large billboards & displayed one line at a time across the country’s highways. I want my friends & family to read it. I want my former & future bosses, old professors, high school teachers, people with whom I haven’t spoken since my diagnosis, the entirety of the federal government, & random strangers on the street to read it. I even want my doctors to read it. If it took me so long to understand what it means to live with a disability, how could I expect anyone else to understand? And, if they couldn’t understand, how could I expect empathy, appropriate accommodations, and equal accessibility for all people with chronic & invisible illnesses or disabilities?

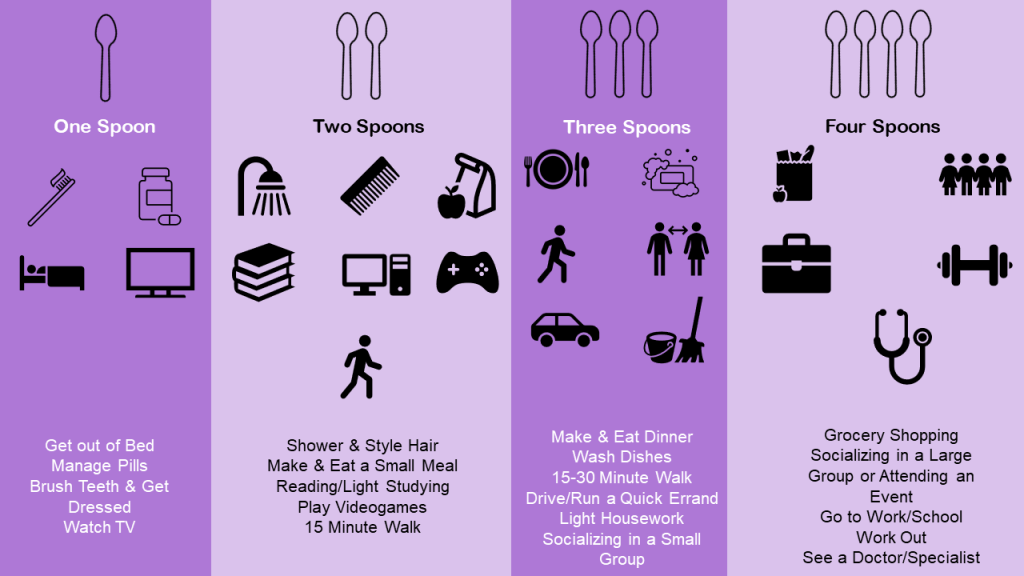

Spoon theory, in short, uses spoons as a metaphor for energy, and as an analogy for possibilities. As a healthy person– especially a young & healthy person– you wake up with an unlimited number of spoons, and, therefore, an unlimited number of possibilities. If you use one of your infinite spoons to brush your teeth & get dressed, and toss another two spoons out for taking a shower in the morning, your ability to go to work or to cook a meal later that day isn’t affected. There is usually no external force, outside of time constraints, that would cause you to need to choose between the two. You still have infinite spoons.

Chronic illnesses and disabilities limit your spoons. In the typical Spoon Theory Model, a person with a chronic illness or disability might start their day with around 12 spoons. Some days I’ll start with more spoons than others. Some days I might wake up with just one spoon. Of course, this isn’t to say healthy people don’t sometimes wake up with a limited amount of spoons; it can happen with the onset of a cold or virus, or even a particularly bad night’s sleep. But chronically sick people wake up every day with a strict spoon budget, and things as small as skipping a meal or getting an hour less of sleep can further limit it.

On a normal day in college, I might have had to use around 20-27 spoons on average. Getting out of bed, brushing my teeth, getting dressed, eating breakfast, taking my meds, and brushing my hair would cost me seven spoons first thing in the morning. If my classes were in the afternoon, I would eat lunch and then walk the 20 minutes to campus, using another five spoons. Classes would cost between 2-4 spoons depending on the length and content. Getting back to the apartment would take another three spoons. Making dinner and washing the dishes would cost another six spoons total. I could sometimes get that six spoons for dinner down to two– microwave burritos or toaster oven taquitos don’t require much energy or any clean-up, so these were often my go-to meals. If I needed to read a paper for a class, complete an assignment, or study for an exam, that would take another two spoons per hour. And finally, two last spoons for showering before getting into bed. At least, that was what I would aim to do every day.

But, I only had 12 spoons, and I was confused as to why I still felt so sick all the time. Often, I would skip class to nap or catch up on assignments, but I would always feel guilty; everyone else was making it to class, and missing a lecture to sleep more made me feel lazy. A slacker. I usually couldn’t stay up studying past 9:00 pm, and if I ever wanted to do something fun on the weekend, I would have to plan for sufficient rest time the day before and after. I was already budgeting my spoons, I just didn’t know it, or know how to properly do it. I knew that I had to approach tasks differently due to Lupus, but I thought I was still supposed to be able to do the same things in a day as before. The Spoon Theory helped me understand and gave me the language to explain why this wasn’t true.

For example, people seem confused by why the suggestion of ‘just working out more’ to help with some symptoms would be so frustrating. Of course, I know working out would help with some of my day-to-day symptoms and add a little boost to help me fend off flares! And, until reading this article, I would feel incredibly weak & fragile for wanting to scream “What?? Are you insane??? I can’t work out on the same day that I have to go to work, or school, or to a doctor’s appointment!”, because– to a healthy person– this sentiment would sound insane! Why can’t you do two common things in one day? Now I can say, “because, I don’t have enough spoons for that!”

The 12 spoon model resonated with what I felt like I could do in a day. If I had a full day of work or school to attend, I wouldn’t have enough energy to go to the gym and shower after also taking care of all the essential activities for every day: eating, dressing, and taking medications. I need to plan how I am going to use my spoons every day to get the things that I both need and want to get done.

I’m still learning that I can’t do it all. That I need to be accommodating with myself and remember to budget my spoons. That, if I over-exert myself and begin to accrue a “spoon debt”, my symptoms will get worse. That my spoons, each day, will become fewer and fewer as all of these factors are compounded. Chronic & invisible illnesses do not go away; those of us who have them, have to think about our physical and mental limits every day. No matter what lifestyle choices we make or medications that we take, our spoons will still be limited.

The CDC estimates that six in ten adults in the United States live with a chronic illness, and four in ten currently live with two or more. But, as a whole, we still operate as if everyone has unlimited energy and possibilities every single day. So much so that it took an analogy involving silverware to help me feel okay about slowing down and allowing myself to rest. The praising of young kids for perfect attendance, the lack of reasonable accommodations for sick students to telecommute or to not be penalized for missing class more often than their healthy counterparts, the fast-paced academic world, the eight-hour workday, the five day work week, & the absence of proper paid sick leave in most professional settings are all examples of how the basic needs of chronically ill people are overlooked or seen as “extra” by today’s ableist culture. This is why I think The Spoon Theory is so important for everybody to understand. We can’t begin to make spaces such as the workplace or academic settings more accommodating for people with chronic illnesses until we understand what it is like to live with one.